The Dr Quine project consists in writing programs capable of printing themselves. It’s an exercise in self-replication. The name comes from the philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine, who gave his name to the concept of quine in computer science. Why this project is both fun… and a real headache

There’s something unique about the Dr Quine project: from a utilitarian point of view, it serves no purpose, yet it’s extremely instructive.

Writing a program that prints itself without cheating (without reading its own source file) is like solving a riddle where the question is also the answer. It’s at once a logical challenge, mental gymnastics, and a test of absolute rigor in the management of character strings, formats (printf) and program structure.

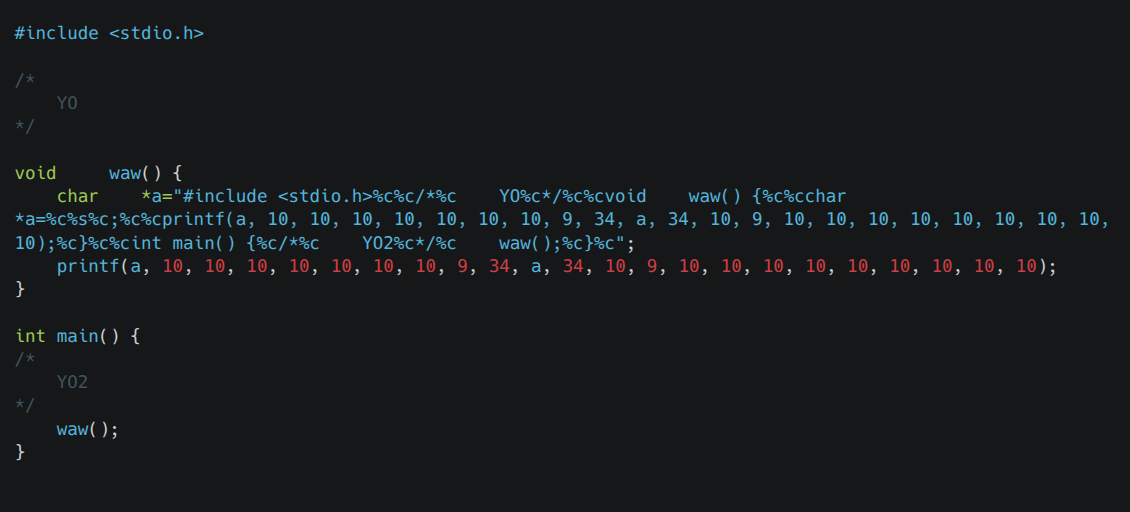

First quine

The Colleen.c program is a quine, i.e. a program that displays exactly its own source code. The principle is simple to say, but tricky to achieve: you have to write a program capable of printing itself without reading its file. To achieve this, the code contains a string that represents the entire program, but with placeholders for special characters such as line breaks or quotation marks.

The program then uses printf to replace these placeholders with the correct characters (\n, “…), and inserts this string into the output. The trick is to be very precise with escape characters and format: a mistake with a quotation mark or line break, and the program won’t print properly. The real challenge is to nest the string within itself: the string contains the code, which contains the string, which contains the code… without an infinite loop.

It gets complicated…

The recurring Quine… with countdown timer

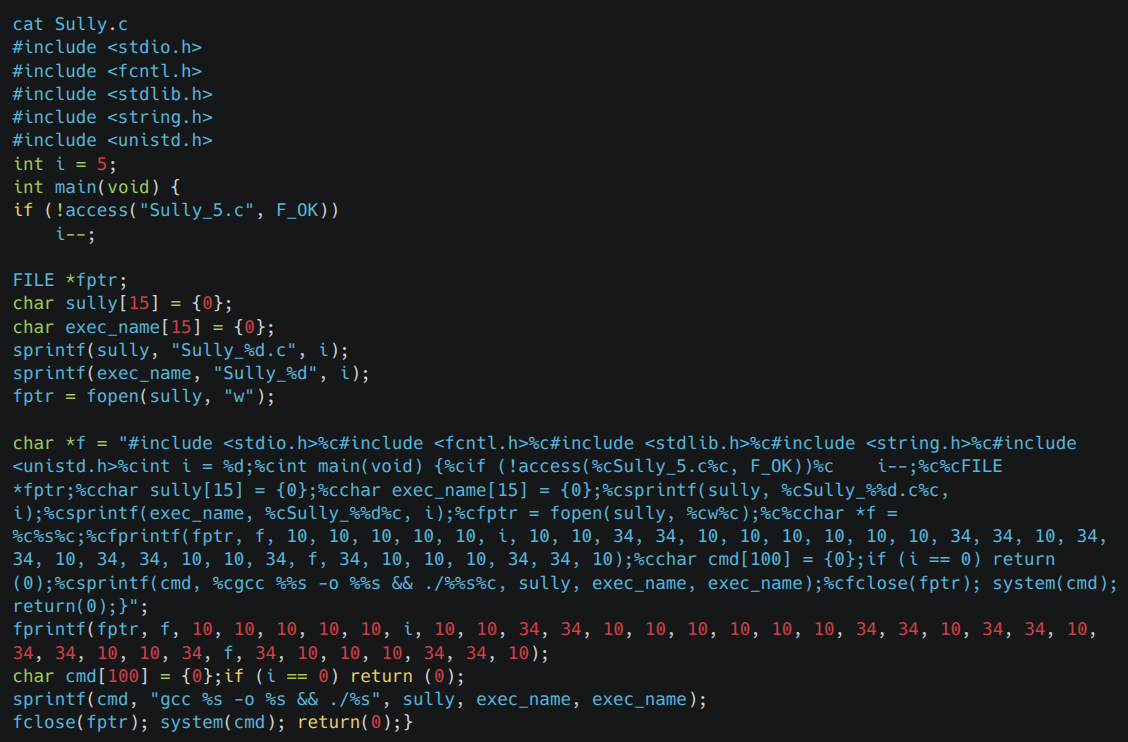

Unlike the classic quine, Sully.c doesn’t just print itself. It generates a new source file, named Sully_5.c, which is itself a quine.

Each time this program is run, it creates a new version of itself, with a decreasing i counter. How does it work?

- The program starts with i = 5.

- It checks whether the file Sully_5.c exists, and if so, decrements i.

- It creates a file Sully_i.c and writes the program’s source code to this file, replacing the value of i with the current value.

- It then compiles and executes this new file.

- This process is repeated until i reaches 0, at which point the program stops.

The subtleties:

- The program has to write its own source code with a dynamic i variable, which complicates the writing of the string that reproduces itself.

- It uses functions such as sprintf to construct file names and system commands.

- The source string (char *f) contains a version of the complete code, with placeholders for special characters, but also for the i variable.

- Careful handling of quotation marks, line breaks and all escape characters in this string is essential.

- The program auto-generates, compiles and executes, forming a reproduction loop.

Even more complicated… quines in ASM x64

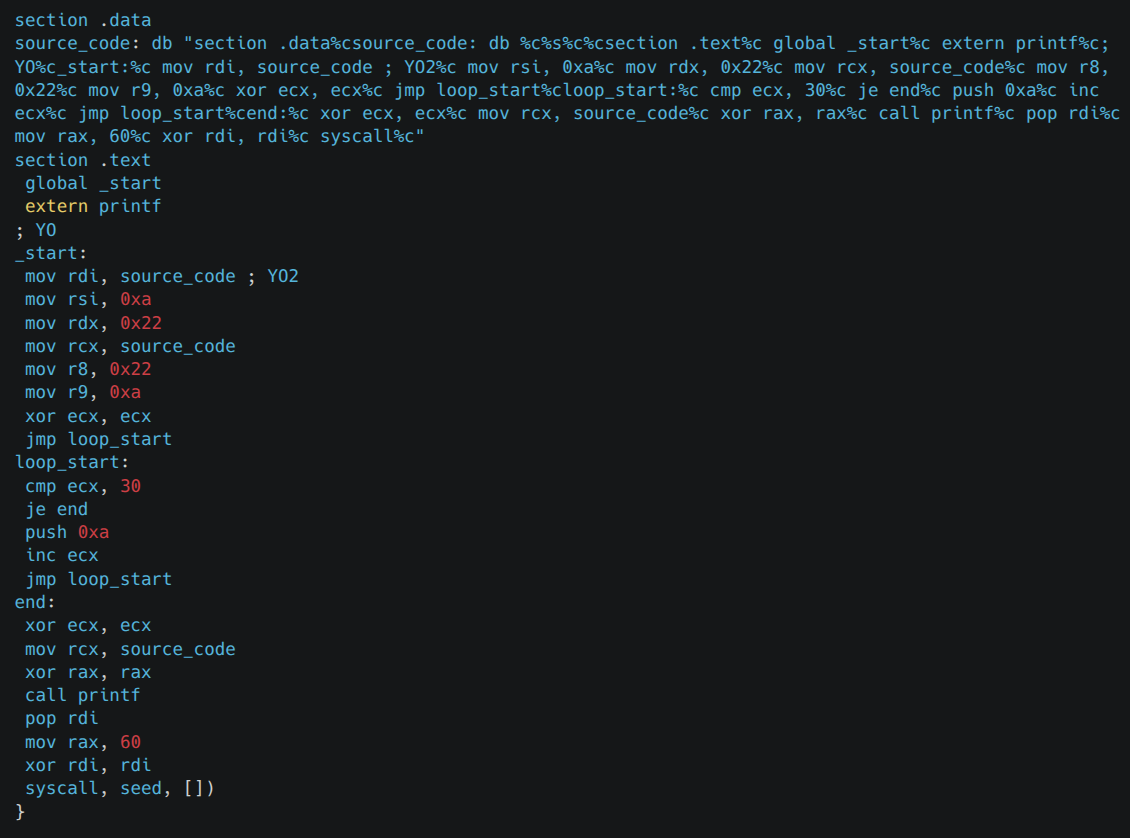

Making a quine in assembler is much more complex than in a language like C. You have to manipulate registers directly, manage memory precisely and code each input/output instruction by hand. The slightest error in address or instruction management can cause the program to crash. What’s more, coding often has to take account of operating system-specific system calls.

This assembler program is a quine: it displays its own source code:

The code is divided into two main sections:

- In the .data section, we find a source_code string containing the complete program text, with placeholders (%c, %s) for special characters and variable parts.

- In the .text section, you'll find the _start routine, which is the program's entry point.

- The routine begins by preparing the registers to call the printf function (imported from libc), passing the address of the source_code string and parameters to correctly format the text (e.g. line breaks and quotation marks).

- Next, a loop is executed to manipulate certain registers and push values to the stack, but its main function is to prepare the parameters and manage the characters to be displayed.

- Finally, the program calls printf to display the source string on the screen, then ends cleanly with a syscall to exit.